Spencer, Wayne (Conservation Biology Institute). 2005. Maintaining Ecological Connectivity Across the Missing Middle of the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor. (PDF – 2.71 MB)

Spencer, Wayne (Conservation Biology Institute). 2005. Maintaining Ecological Connectivity Across the Missing Middle of the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor. (PDF – 2.71 MB)

The Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor is a peninsula of mostly undeveloped hills jutting about 42 km (26 miles) from the Santa Ana Mountains into the heart of the densely urbanized Los Angeles Basin. Intense public interest in conserving open space here has created a series of reserves and parks along most of the corridor’s length, but significant gaps in protection remain.

These natural habitat areas support a surprising diversity of native wildlife, from mountain lions and mule deer to walnut groves, roadrunners, and horned lizards. But maintaining this diversity of life requires maintaining functional connections along the entire length of the corridor, so that wildlife can move between reserves—from one end of the hills to the other.

Already the corridor is fragmented by development and crossed by numerous busy roads, which create hazards and in some cases barriers to wildlife movement. Proposed developments threaten to further degrade or even sever the movement corridor, especially within its so-called “Missing Middle.” This mid-section of the corridor system, stretching from Tonner Canyon on the east to Harbor Boulevard on the west, includes several large properties proposed for new housing, roads, golf courses, and reservoirs. Such developments would reduce habitat area and the capacity to support area-

Already the corridor is fragmented by development and crossed by numerous busy roads, which create hazards and in some cases barriers to wildlife movement. Proposed developments threaten to further degrade or even sever the movement corridor, especially within its so-called “Missing Middle.” This mid-section of the corridor system, stretching from Tonner Canyon on the east to Harbor Boulevard on the west, includes several large properties proposed for new housing, roads, golf courses, and reservoirs. Such developments would reduce habitat area and the capacity to support area-

dependent species and, if poorly designed, could block wildlife movement through the corridor.

This report builds on an impressive array of previous ecological and wildlife movement studies in the Puente-Chino Hills, as well as the general literature on wildlife movement corridors as it applies to this unique peninsula of wildness. It supplements the existing information with an analysis of gaps in protection—with special focus on the vulnerable Missing Middle—and recommends conservation and management actions to prevent further loss of ecological connectivity and retain native species.

Schlotterbeck, Melanie. 2001. GIS Mapping of Biological Studies in the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor Including Species Diversity and Relative Abundance. (PDF – 7.9 MB)

Schlotterbeck, Melanie. 2001. GIS Mapping of Biological Studies in the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor Including Species Diversity and Relative Abundance. (PDF – 7.9 MB)

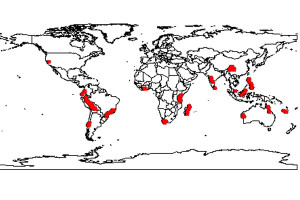

Known as a global “hotspot” of biodiversity because of its unique and threatened flora and fauna, some areas of southern California are becoming islands of habitat. The Puente-Chino Hills, on the eastern side of the Los Angeles Basin, provide an excellent example of an ecosystem at risk. Government agencies, concerned citizens, and researchers are drawn to the region for several reasons: its biodiversity, its beauty, and to understand what is at risk of extinction. Four important biological studies have been conducted in the hills in the past few years. These include vegetation, carnivore, herpetofauna, and avian studies. Only the vegetation and avian projects included digital maps.

This project has put into digital form both the carnivore and herpetofauna studies through the use of geographic information systems (GIS). For both studies, themes were created for each scat transect and track station (used in the mammal study) and each pit-fall trap array (used in the reptile study). Themes included both a presence/absence layer as well as a detailed relative abundance layer. To determine the species diversity of the Corridor, the Shannon-Weiner diversity index was utilized, as it is commonly used as a measurement for diversity among ecological communities and to assess impacts of disturbances. During this mapping project, various corridor types (box and arch culverts, underpasses, equestrian, and service tunnels) were identified and individually mapped along all roadways bisecting the Corridor.

The importance of this mapping project is three fold. First, it added two significant layers of detailed information to an existing GIS mapping project currently underway at Whittier College. Second, it helped two completed studies (by Crooks and Haas, Case and Fisher) become compatible with other projects layers. Finally, it will become a historical documentation of species once found in the Puente-Chino Hills. These themes have been integrated into the mapping project at Whittier College, under the guidance of Dr. Cheryl Swift, and have been made available to various agencies such as the Wildlife Corridor Conservation Authority and California State Parks.

The importance of this mapping project is three fold. First, it added two significant layers of detailed information to an existing GIS mapping project currently underway at Whittier College. Second, it helped two completed studies (by Crooks and Haas, Case and Fisher) become compatible with other projects layers. Finally, it will become a historical documentation of species once found in the Puente-Chino Hills. These themes have been integrated into the mapping project at Whittier College, under the guidance of Dr. Cheryl Swift, and have been made available to various agencies such as the Wildlife Corridor Conservation Authority and California State Parks.

Biological corridors connecting the fragmented habitats are one important remedy in the management of these hills and preservation of its natural processes. Without connections to viable habitats the wildlife in the Puente-Chino Hills will become island populations. The habitat will lose its diversity of species and eventually become a landscape devoid of many endemic inhabitants. If that is the case, this mapping project will have documented what was once here, or be used in finding solutions to the situation.

Schlotterbeck, Jennifer. 2003. Considering Impacts to Wildlife Corridors Under the California Environmental Quality Act: Effects in the Whittier-Puente-Chino Hills.

This article explores the concept of the “wildlife corridor” as a means of protecting biological diversity in California. The works of prominent conservation biologists are described, along with the efforts of Southern California conservationists to preserve biodiversity in the Whittier-Puente-Chino Hills by connecting large swaths of open space with corridors through which various species can migrate. The article posits that the veracity of wildlife corridors is well accepted in the scientific community, but that conservationists, despite having various legal means at their disposal to protect open space, are still at a disadvantage when it comes to protecting wildlife species. The article further suggests that the conservation of biological diversity is a policy goal under the California Environmental Quality Act. It then proposes that an amendment to the CEQA Guidelines mandating consideration of impacts to wildlife corridors, defining those impacts, and suggesting mitigation measures is legally justified. Finally, the article proposes exact language for the amendment, as reviewed by leading biologists in the field, and demonstrates how such an amendment would benefit the Whittier-Puente-Chino Hills.

This article explores the concept of the “wildlife corridor” as a means of protecting biological diversity in California. The works of prominent conservation biologists are described, along with the efforts of Southern California conservationists to preserve biodiversity in the Whittier-Puente-Chino Hills by connecting large swaths of open space with corridors through which various species can migrate. The article posits that the veracity of wildlife corridors is well accepted in the scientific community, but that conservationists, despite having various legal means at their disposal to protect open space, are still at a disadvantage when it comes to protecting wildlife species. The article further suggests that the conservation of biological diversity is a policy goal under the California Environmental Quality Act. It then proposes that an amendment to the CEQA Guidelines mandating consideration of impacts to wildlife corridors, defining those impacts, and suggesting mitigation measures is legally justified. Finally, the article proposes exact language for the amendment, as reviewed by leading biologists in the field, and demonstrates how such an amendment would benefit the Whittier-Puente-Chino Hills.

Editor’s Note: This article was published Ecology Law Quarterly in the February 2004.