Given the complexities of law, politics, and government, a synopsis of the planning process may be useful for interested citizens.

GENERAL PLANS, ZONING, AND “SPHERES OF INFLUENCE”

GENERAL PLANS, ZONING, AND “SPHERES OF INFLUENCE”

General Plans

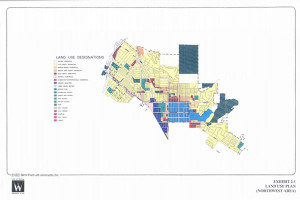

Each city has a General Plan that lays out which areas will be residential and which will be commercial, industrial, or open space. General Plans are important because they determine the sizing of the infrastructure, for example, how wide the streets are or how big the sewer pipes are. General Plans are supposed to be updated every 10 years and they can only be changed a certain number of times a year.

Zoning

Each city also has a zoning map which is a more specific delineation within the General Plan. The city assigns the zoning if the land lies within the city limits. The county assigns zoning if the land lies outside of a city boundary.

Jurisdiction Over Land Use

Land near a city but outside of its city limits, is probably within the city’s Sphere of Influence (SOI). When lands are in an SOI, it means they will ultimately probably become part of the city. SOI’s are usually determined by the closest provider of services (police, water, sewer, etc.). The city can “pre-zone” land for development in its SOI. If developers don’t feel they are getting a fair shake with a city, depending on the property, they can have services such as electricity, water, and sewer provided by the county instead, thereby avoiding controls put in place by a city’s General Plan.

PLANNING BY THE DEVELOPER

Landowner Rights

Landowners carry a certain expectation of economic return or value based on what zoning the city or county has assigned to it. They are entitled to a “reasonable economic return” on their investment in land.

Development of Housing Plans

If landowners want to develop their land, they hire a planning firm that goes about developing plans for the land, based, in part, on the zoning allowed and their profit goal. The land may be zoned commercial, light industrial, residential, or agricultural. Residential zoning is usually what everyone is concerned about because of the impacts on infrastructure (roads, sewers, water) and services (trash collection, police, schools).

Constraints Analysis

Constraints Analysis

Residential land could have very low density (1 housing unit per 40 acres or 1 unit per 5 acres) and would be considered rural residential. Or it may have very high density (30 units per acre) which would be an apartment complex. Landowners may try to stay within the zoning allowance for their projects or they may ask for a variance, which allows, for instance, more density (more housing units per acre) or the addition of a commercial area. The landowner factors in the difficulty of approval of the project. Does the city council look dimly on development? Is there an active citizenry that opposes the development? Are environmental organizations lining up to oppose it? Opposition may cause delays that developers consider in their original plan. They may also size up the community and offer to pay for extra amenities like a new school, a park, historical preservation site, or a widened road. Developers almost always hire someone from the community to be their spokesperson for the project.

Land Surveys

The landowner’s planning consultant team members survey the land to see what constraints exist on it topographically (e.g., steep canyons), biologically, geologically, etc.

More Constraints

There are other overlays on the property besides zoning which constrain its use: the presence of endangered species, earthquake faults, landslides, tar seeps, or neighboring uses. The city may enact further restrictions on building. For instance, it may forbid construction on ridgelines or prominent rock outcroppings. The Army Corps of Engineers is called in if a development may negatively impact stream beds or flood zones. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has jurisdiction over federally listed Endangered Species (which are present at various locations throughout the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor), while the California Department of Fish and Game has jurisdiction over species on the state’s Endangered Species list and on stream beds.

Plan Submission

Once the plans for development are ready, they are submitted to the city or county planning department. It begins reviewing and processing the plan. The planning department may or may not like the plan but it must process the plans within a certain state-defined timeframe.

THE CALIFORNIA ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY ACT

THE CALIFORNIA ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY ACT

The Environmental Impact Report

When the completed plan is received (with all necessary documentation) and the landowner wishes to proceed, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) process is triggered. CEQA stands for the California Environmental Quality Act. CEQA was written to require that important information be made available to the decision makers (planning commissioners, city council members, or county supervisors) regarding the impacts of any given project and whether the impacts can be mitigated (fixed/ameliorated). This information is reported in the form of an Environmental Impact Report (EIR).

Purpose of the EIR

The purpose of an EIR is to inform decision makers about impacts, not to stop projects. For example, in a project that might be built in an area of unstable soils and landslides, the city council or board of supervisors could nevertheless determine that the economic benefits of housing construction are more important than potential risks to future homeowners. In such a case, decision makers can make a finding called a “Statement of Overriding Consideration,” thus allowing the planned project to proceed despite the environmental hazards.

Requirements of CEQA

Requirements of CEQA

The CEQA specifically requires a number of items to be assessed and provides the minimum framework for review and timing. It was also written to require citizens to pay attention. If citizens don’t believe a CEQA document is adequate, they can sue and ask the courts to decide. The strength of their case, in part, hinges on their participation in the process from the start. They can’t come in at the last minute and try to sabotage a project.

Lead Agency

The “lead agency” for the CEQA process, which in our case is usually a city or county, initially makes a determination as to whether an EIR is even necessary. Some cities or counties try to let the developer off the hook by not even requiring an EIR. Or they may require a minimal look at impacts and allow a Negative Declaration (of significant impacts) or a Mitigated Negative Declaration. If they decide an EIR is called for, the law is very specific about what has to be included in it: it has to assess traffic, geology, noise, air pollution, biological resources, etc. It also lays out a minimum timeframe for the various stages of this process.

EIR Alternatives

Any given development plan is (1) supposed to avoid negative impacts, (2) minimize negative impacts, or (3) mitigate them if they can’t minimize or avoid them. Landowners look at mitigation as an expense of doing business. Opponents of projects often look at mitigation as merely a Band-Aid. There are ways to mitigate off-site as well as on-site (a kind of mitigation horse-trading). For instance, landowners could destroy an oak woodland on their land in exchange for buying and permanently protecting an oak woodland elsewhere. Regulatory agencies prefer mitigation on-site.

Lead Agency Options

Lead Agency Options

When the city is the lead agency, it usually hires the consultant team and is reimbursed by the developer for the costs of preparing the EIR.. When the county is the lead agency, it often allows the developer to hire the consultant. The quality of the EIR depends on the quality of the consultants. Some “hired guns” white-wash the issues, while others are quite thorough. Neither Orange nor Los Angeles County have a very good reputation for thoroughness. EIR consultants have been known to slant information in favor of the proposed project because ultimately their future business depends on their acceptability both to the landowner (who foots the bills) and to cities or developers who hire them.

Notice of Preparation of an EIR

After determining if an EIR is necessary, the EIR consultant team sends out an initial Notice of Preparation (NOP), which informs the citizenry and interested parties (like the Metropolitan Water District or neighbors to the project) that an EIR is on its way. The purpose of the NOP is to bring forth for study additional significant information that may not yet have been identified. The law does not require a public scoping meeting but they are usually held to make it appear that the process has invited public input.

Input from Other Agencies

Some state agencies are required to comment on all EIR’s because of their regulatory mandate under the law. For instance, Fish and Game is required to protect species, CalTrans is required to pay attention to traffic. State Parks is considered, under CEQA, to be a trustee agency; hence it too is required to comment on EIR’s that affect its properties.

Gathering of Information

Gathering of Information

After the NOP hearings are held, the EIR consultants begin their assessment of the impacts. They write a Draft EIR, which is circulated to all of the interested parties. A timeframe for responding to this is also established by law. The bigger the document the longer the time frame is required for public scrutiny.

Levels of Significance

EIR’s determine if there is a significant impact on something (for example additional cars on a street at peak hours). If there are significant impacts, mitigations are proposed. The EIR consultants then assess (make an educated guess) whether the mitigation enacted brings the impact below a level of significance. The EIR specifically has to compare various levels of development including a “No Build” alternative. It also has to address “cumulative impacts.”

Citizen Input

The Draft EIR is then circulated for comments by all interested parties. Citizens and agencies make comments and ask for accommodation to their particular interest (e.g., CalTrans may want a traffic light, re-striping, or a turn lane). Citizens generally try to poke holes in the adequacy of the EIR if it displays major flaws in assessing impacts.

Public Hearings at the Planning Commission

Usually at this point the project is brought before the city or county planning commission for hearings. The role of the commission is to make recommendations to a city council or county board of supervisors. It takes testimony, reviews the EIR, and the development plans and makes a decision to accept or deny the development proposal. Citizens should be involved at this level of decision making in order to raise issues.

Public Hearings at the City Council or Board of Supervisors

Public Hearings at the City Council or Board of Supervisors

The city council or board of supervisors then goes through the same process of hearings with the goal of assessing whether each of the impacts identified in the EIR are adequately addressed. It makes a finding that the EIR is adequate or not. If the council/board of supervisors approves the EIR, it is then re-circulated as the Final EIR. If citizens are unhappy they may sue the city/county on the grounds that the EIR was not adequate.

FINAL APPROVAL OF DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS

Once the EIR has been approved, other sets of approvals also occur which give the go-ahead on the project. This may include a General Plan Amendment, a Development Agreement, and Tentative Tract Maps. Some of these are subject to a citizen referendum. This means that if citizens object to the approval of a project, they have recourse through the ballot box. The vote on such a ballot issue carries the rule of law — but only for one year.

What Residential Development Means To the Taxpayer

What Residential Development Means To the Taxpayer

Many cities/counties still view residential development as inevitable; in fact, they think it is positive because they mistakenly believe it generates revenue. Such thinking is simply erroneous. Residential development has never paid for itself. Short-term revenue generated by development fees is a small fraction of the total cost to a community in terms of services which must be provided later and forever – by taxpayers who are often surprised to learn that they – not the developer – are responsible for financing much of the additional infrastructure (schools, water systems, police, and fire protection, etc.) that housing developments require.

Developer Strategy

Once the approval for housing is in place, the price of the land escalates dramatically. Many developers in the State of California have thus recognized that pursuing housing “entitlements” (approvals to build housing by the city or county) is a way of artificially inflating the value of the land they never intended to develop because of its inherent difficulties (for example, landslides, pollution, poor access). These lands are frequently the targets of intense environmental interest.

Entitlements

Developers are aware of the growing interest of Californians in preserving their landscape. The “entitlement game” has thus become a mechanism whereby developers attempt to acquire permission to build housing tracts before negotiating a selling price for their land that will ultimately be purchased with taxpayer dollars. When city or county governments grant entitlements in the face of overwhelming environmental and citizen objections to a project, it is an indirect way for them to transfer public funds (in the form of State Park Bond money, etc.) to private enterprise. In this way city or county elected officials may be favoring the financial interests of big developers over the well-being of their constituents.

Political Will

Political Will

Responsive and responsible public officials are becoming increasingly aware that communities may have an alternate vision for land use other than housing developments. But it takes political will on their part to preserve these lands. Nothing helps them develop this political will more effectively than citizen participation in the process. While many of us may feel that having influence in state and national politics is out-of-reach, local decision making is well within the sphere of the average resident. Let your voice be heard. The Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor has been preserved because residents up and down its boundaries have insisted on responsible decision making from their local elected officials. Coordinated citizen action can make the preservation of our local heritage a reality.

When people begin to accept that success is possible, it becomes virtually inevitable.