Below is a list of frequently asked questions. If we haven’t answered your question and you can’t find it in another section of the website, please email us.

- What is the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor?

- Why is it important to keep the natural lands connected?

- What kinds of plants are found here?

- What kinds of animals are found in the Corridor?

- What is a Hot Spot of Biodiversity?

- What is Habitat Fragmentation?

- Why are there so many species in the Corridor?

- How do we know what types of animals live in the Corridor and where they move?

- Since the Corridor is crossed by a number of roads (e.g., Colima, Hacienda, Harbor, the 57 and 91 freeways) don’t these roads make it impossible for animals to cross?

- How is the Corridor to be protected?

Q – What is the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor?

Q – What is the Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor?

A – This landscape (shown in light blue in the photo from space, shown right) lies at the juncture of Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, and Riverside Counties. It serves as the visual backdrop for millions of Californians. The Wildlife Corridor is a 31-mile long area of natural lands that remain as open space and are still connected throughout this hillside system. It stretches from the Whittier Narrows area near the 605 and 60 freeways all the way to the Cleveland National Forest south of the 91 freeway. Eighteen thousand acres are protected in public ownership but thousands more are threatened by development that could sever the Corridor. View a Map of the Corridor.

Q – Why is it important to keep the natural lands connected?

Q – Why is it important to keep the natural lands connected?

A – Animals migrate throughout the Corridor in search of food, mates, and “home” territory. If the Corridor is severed by housing developments or new roads, the wildlife will be unable to roam throughout the hills. Over time, as they lose their ability to find mates and safe private areas for their nurseries, they will eventually die out. Fragmented habitat is not healthy habitat. The larger publicly owned and protected areas such as the Whittier Hills Open Space, Powder Canyon, Schabarum Park, Chino Hills State Park, and the Cleveland National Forest provide the main breeding grounds and “home” territories. To insure the long-term health of the hillside ecosystem, these parklands need to be permanently connected together with publicly protected open space.

Q –  What kinds of plants are found here?

What kinds of plants are found here?

A – Vegetation grows in communities. These communities include walnut woodland, oak woodland, southern willow scrub, freshwater marsh, riparian (streamside), grasslands, and coastal sage scrub. Each vegetation community supports a variety of wildlife that find food, safety, and homes among the particular kinds of plants and trees that grow there.

Q –  What kinds of animals are found in the Corridor?

What kinds of animals are found in the Corridor?

A – Both common and unique species live in the Corridor. Some of the more common animals include deer, coyotes, foxes, bobcats, hawks, owls, opossums, raccoons, and gray squirrels. In addition, hundreds of other species including many rare and/or endangered species live in this hillside system. It is part of an area known as a global ” Hot Spot of Biodiversity.”

Q –  What is a Hot Spot of Biodiversity?

What is a Hot Spot of Biodiversity?

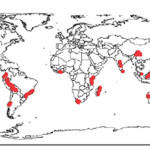

A – Scientists have designated 20 worldwide “Hot Spots.” These are places rich in species diversity, yet are threatened by imminent development. The Puente-Chino Hills Wildlife Corridor is situated in one of these Hot Spots. This Hot Spot is an area second only to tropical rain forests in both diversity of species and threat.

Q  – What is Habitat Fragmentation?

– What is Habitat Fragmentation?

A – Habitat Fragmentation is the alteration of the natural environment that leads to a loss of both plant and animal species. Fragmentation can occur from something as small as a trail or as narrow as train tracks to something as large as agricultural fields, a housing development, or a freeway. When habitats are fragmented into smaller and smaller patches, the natural systems and animals and plants no longer have the necessary environment needed to successfully reproduce. They will, therefore, likely eventually die out.

Q – Why are there so many species in the Corridor?

A – This is an ancient landscape. No glaciers scraped their way into the terrain here. The plants and animals that live here have had a long time to evolve. That gift of time gave them a chance to differentiate into an astonishing array of species. Throw in the warm Mediterranean climate and you have both a crucible and an Eden for unusual and rare creatures. The gift of geologic uncertainty (earthquakes) provided them with many opportunities to change. This calliope of movement created hills, mountains, and slopes that allowed plants and animals to move around into new niches creating many endemic species (species found nowhere else). For example, Iowa has no endemic species (species only found in Iowa) while California has over 2200.

A – This is an ancient landscape. No glaciers scraped their way into the terrain here. The plants and animals that live here have had a long time to evolve. That gift of time gave them a chance to differentiate into an astonishing array of species. Throw in the warm Mediterranean climate and you have both a crucible and an Eden for unusual and rare creatures. The gift of geologic uncertainty (earthquakes) provided them with many opportunities to change. This calliope of movement created hills, mountains, and slopes that allowed plants and animals to move around into new niches creating many endemic species (species found nowhere else). For example, Iowa has no endemic species (species only found in Iowa) while California has over 2200.

Q – How do we know what types of animals live in the Corridor and where they move?

A – Interested agencies have funded multi-year studies of mid-level predators (coyotes, bobcats, raccoons, foxes), avifauna (birds), and herpetofauna (reptiles). Other studies are still being conducted on the various plant and animal communities in the hills as well as the usefulness of underpasses for wildlife movement. Some of the results of these studies have been compiled into Geographic Information System (GIS) maps. Groups like the Audubon Society have provided information reaching back 50 years that document bird habitat and migration paths.

A – Interested agencies have funded multi-year studies of mid-level predators (coyotes, bobcats, raccoons, foxes), avifauna (birds), and herpetofauna (reptiles). Other studies are still being conducted on the various plant and animal communities in the hills as well as the usefulness of underpasses for wildlife movement. Some of the results of these studies have been compiled into Geographic Information System (GIS) maps. Groups like the Audubon Society have provided information reaching back 50 years that document bird habitat and migration paths.

Q –

Since the Corridor is crossed by a number of roads (e.g., Colima, Hacienda, Harbor, the 57 and 91 freeways) don’t these roads make it impossible for animals to cross?

A – All of these roads, to a greater or lesser extent, do provide a barrier to wildlife movement. Improved movement potential needs to occur on several roads to cut down on roadkill and dangers to drivers. Yet motivated by an internal drive to find their own way in the world and find new mates, animals can and do cross these roads either through culverts or at street level.

A – All of these roads, to a greater or lesser extent, do provide a barrier to wildlife movement. Improved movement potential needs to occur on several roads to cut down on roadkill and dangers to drivers. Yet motivated by an internal drive to find their own way in the world and find new mates, animals can and do cross these roads either through culverts or at street level.

There are very large underpasses that the animals can use at the 57 and 91 freeways. Colima Road also has an underpass (on the old Chevron property) although it is somewhat narrow for optimal movement. Because Hacienda Road is not a wide street it does not provide the same barrier as larger streets. In addition, there is a small culvert under the road that some small animals use.

The most challenging crossing had been at Harbor Blvd. The width, volume of traffic, and speed on Harbor caused many animals to be killed each year not to mention threats to driver safety. A new undercrossing was completed in June 2006. Wildlife biologists predicted it would take up to six months for deer to use the underpass. However, within nine days of its official opening, deer were photographed moving through the new retrofitted tunnel (see photo right). Since then a number of other wildlife including coyote, raccoons, and rabbits have been photographed using the Harbor Blvd. underpass.

The most challenging crossing had been at Harbor Blvd. The width, volume of traffic, and speed on Harbor caused many animals to be killed each year not to mention threats to driver safety. A new undercrossing was completed in June 2006. Wildlife biologists predicted it would take up to six months for deer to use the underpass. However, within nine days of its official opening, deer were photographed moving through the new retrofitted tunnel (see photo right). Since then a number of other wildlife including coyote, raccoons, and rabbits have been photographed using the Harbor Blvd. underpass.

Q –

How is the Corridor to be protected?

A – There are many entities working cooperatively to preserve the land, from local grassroots groups to national conservation organizations; and local decision-makers to state and federal agencies. View a list of Interested Government Agencies.

A – There are many entities working cooperatively to preserve the land, from local grassroots groups to national conservation organizations; and local decision-makers to state and federal agencies. View a list of Interested Government Agencies.